MultiMachine, an open-source machine tool. The combination of a MultiMachine and a welder can be used to build different types of metal. Building your own lathe.

Throw a stone at any large gathering of makers, and you’re likely to hit somebody who owns a set of DIY-savant on building your own machine shop by casting scrap aluminum, melted in a charcoal-powered bucket furnace, into sand molds formed by wooden patterns. I’ve owned a set myself, for more than a decade, and “at least starting on the lathe,” which is the first tool in the series, has been on my someday list since the first time I ever saw the books advertised in Lindsay Technical Books’ classic ad in Popular Science. Ask a thousand people who admit to owning the books, however, if they’ve actually made that start, and you’d be lucky to get one emphatic yes.

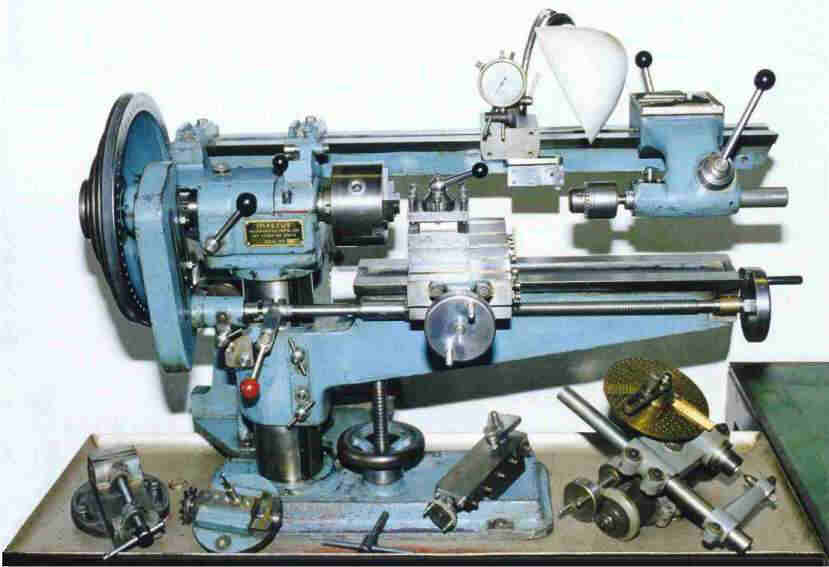

Lionel Oliver II, on the other hand, whose amateur sandcrabbing website is probably the single greatest online resource for those interested in small home foundry work, has not only made a meaningful start, but gotten most of the way through the build. And, perhaps most importantly, he’s. Oliver’s page has done a lot to inspire others around the web to take up the Gingery lathe project for themselves, but due credit has to go to folks like southern California resident, whose lathe, pictured above, was apparently complete as early as 1998. Barry also built the Gingery metal shaper from book 3 of the series. Likewise for Nebraskan Bill R., whose was most recently updated in 1999 and includes this photo of his lathe turning a boring bar that will later be used to bore its own tailstock. Hp Laserjet 3030 Scanner Software For Vista there.

If you delve deep enough into the dark corners of DIY and metalworking websites, you’ll come across a name that’s either treated with hushed reverence, or outright derision, with very little middle ground. This name is Dave Gingery. I’ll let my colors fly – Dave Gingery was a genius.

First, some history: Dave Gingery wrote a series of books back in the 80’s about building a metal working shop, from scrap. He starts with instructions on building a foundry. Then, using the foundry and some extremely basic metal working techniques, you build a lathe using aluminum sand castings, which you then go on to use to build a metal shaper, mill, drill press, and a plethora of other goodies & attachments. The anti-Gingery crowd will argue vehemently that the machines are inferior, you can’t achieve the same level of accuracy or speed of a decent purchased machine. And they’re not entirely wrong, you’ll never be able to work as quickly with a Gingery lathe as you could with a machine from a reputable manufacturer, and it will be much harder to hold the same tolerances.

Well whoopdie do. I don’t need a metal lathe. I want one, but I don’t need one. I don’t do production work, the only use I have for a lathe is my own shop projects. For me, the process of building a lathe isn’t just a means to an end, its an end in and of itself. If I do my part right, the machine will be capable of holding a one thou tolerance, which is far more accurate than I’m likely ever to need. So that’s my story and I’m sticking to it, and here begins my foray into the wonderful and quirky world of Gingery.

The first challenging casting was the lathe bed. This casting required a special flask (the wooden form that holds a sand mold), which I slapped together a bit differently from what is recommended in the book. I used a series of drywall screws driven into the interior to help hold the sand in place which worked nicely. Here you can see the open sand mold.

The bumps on the bottom part form cavities in the casting. You can also see the drywall screws I put in the cope (top half of the mold) to keep the sand from falling out when I lifted it off to extract the pattern. This was easily the hardest thing I’d ever molded before. This being a pretty challenging casting, I took no chances and made sure all the scrap I melted down was from parts that were originally manufactured via casting, this ensured my shrink rate would be as low as possible and give me the best shot at a good part.

After the pour, I waited a bit for everything to solidify and dumped it out into my wheelbarrow to see how it worked. I was pretty surprised I was able to get a good part on the first shot, I really expected I’d have to take a couple tries to get a good casting on this one. At this point, the book has you hand scrape the top surface dead flat to accept the cold drawn steel ways.

I had expected to have to do this, which is why you can see the two ridges along the top surface, this was to relieve the mating surface and minimize the amount of hand scraping required. Carta Semilogaritmica 6 Ducati Pdf Printer. As it turned out though, a machinist at work offered to mill it flat for me. This saved many hours of labor on my part.

Menu

- ✔ Authentic Happiness Martin E P Seligman Pdf Printer

- ✔ Free Apps For Hp Touchpad Webos

- ✔ Hp Pavilion Laptop Drivers For Windows Xp

- ✔ Epson Perfection 1640su Vista

- ✔ Download Aplikasi Buat Hp Samsung Champ Duos Wifi

- ✔ Hp Design Software Project Runway

- ✔ Hp Laserjet M1522 Mfp Scanner Driver Mac

- ✔ Download Xml File Php